Not If

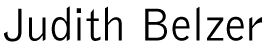

While hiking along the Northern California coast in January of 2022, my companion and I noticed an unfamiliar wave pattern in the ocean. Instead of the usual random breakers, we saw water thrusting toward shore in what looked like mechanical pulsations, organized evenly in lockstep intervals. We remarked on the eerie scene but didn’t make sense of it until we reached home and the internet and learned that there had been a powerful underwater volcanic eruption in the Pacific Island nation of Tonga, thousands of miles away. Tsunami warnings were triggered for a vast swath of territory bounded by the Pacific Ocean, the western US coast included. Though the tsunami never materialized, the eruption’s spooky aftereffects were clearly visible in the rhythmically energized ocean waters. Online drone images of the eruption showed a vast, billowing cloud– a mysterious and muscular form. The images stuck with me.

As did a conversation I had around the same time about another experience of volcanic eruptions. Huh- what was in the air? A recent architecture school graduate described her thesis project to me one late spring day, a few months after the Tongan event. Her project proposed the creation of an elegant catchment system to address the massive ash fallout generated by one of Indonesia’s many volcanos–Mt Merapi –when it erupts at erratic but not infrequent intervals. My friend, herself Indonesian, explained that the design was meant to, in part, protect the subsistence farmers who live in the shadow of Mt Merapi from the dense and potentially fatal ash cloud that blankets the area during and after eruptions. Despite the constant threat to their existence, the farmers continue to live in the zone of the volcano because of the extraordinary soil fertility generated by its emissions.

I wondered aloud to my friend about how these farmers manage the profound uncertainty of a life beneath Mt Merapi. The area’s locals have a fatalistic attitude, she explained, a kind of matter-of-fact frankness about the nature of their existence. Given little choice, they live in relative equanimity, in conditions of predictably unpredictable existential threat.

Today more than ever, we all live in the shadow of Mt Merapi, in circumstances of uncertainty. True, there is a vast difference in the degree of threat we face in our everyday lives. Power and wealth can protect some of us to some extent but, increasingly, even these advantages are undermined. Climate change has, it seems, democratized disaster. This made me think about what we might have to learn from the Indonesian farmers about how to live in the face of atmospheric events and associated societal upheaval that now destabilize human experience across the globe.

The best way for me to explore these questions is in the studio. I’ve been working on paintings and drawings in a series called “Not If.” For me, the central question is no longer IF profound disruption will occur, but WHEN will it next occur and how we will manage it. Would a Venn diagram representing the timing of life-altering events both natural and man-made reveal more overlap than ever before? In a sense, time feels as if it is collapsing. The long arc of geological time collides with the accelerating time of climate change, together contributing to new scenarios of disruption, dislocation, destruction, and transformation.

To explore this phenomenon, I have brought imagery of several types of atmospheric events into my work. I am investigating clouds of all sorts—ash, gas, steam, fog, smoke, chemical, miasmic, vaporous, etc.—that appear, often hovering above or around a gaping orifice that evokes sites as various as volcano mouths, nuclear reactor cooling stacks, gun barrels, sink-hole maws, eyes of storms and even petri dishes. The clouds are at once a product and a display of instability and transformation and suggest not only the far-reaching drift of emissions, both toxic and harmless, but also of our thoughts about the threat they may or may not pose. What is a cumulus cloud and what is an airborne toxic event?

Carriers of their own metaphorically rich history in the realms of art, nature and society, clouds are also everyday occurrences that offer wide-open opportunities for private daydreaming and projection. Weather systems generate them as do as do other kinds of events–explosions, geothermal energy fields, fracking, wildfires, power plants, and volcanic activity, to name a few. At times incipient and wispy and at others fully and expansively formed, clouds, at least since the industrial revolution, can signal both benign and threatening events. I’m drawn to their potential for multivalent meanings.

The “Not If “paintings deploy various perspectives to consider the atmospheric event. Some of the imagery is frontal, some as if surveilled from above by drones or from within and below. Brimming with energy, the clouds/emissions in these paintings are often muscular and dynamic, soft things made unnaturally firm. The expected weightlessness of clouds isn’t always realized. Unknown matter that generates airborne events can lend gravitational pull and hold shapes as if in suspended animation. Appearing at once soft and hard, clouds can develop a well-formed structure but can just as easily dissipate in an instant. The paintings suggest that something almost alchemical is occurring in these transformations. Whether these occurrences are destructive or generative remains uncertain. Pushing to enhance the ambiguity of my imagery, I use a range of formal tools to complicate matters: colors range from organic to chemistry-set strange; the materiality of the paint surfaces alternates between transparency and opacity; figure/ground relationships shift and reverse unexpectedly. Nothing is fixed.

More uncertain than ever is how I feel as I move through my days. With the “Not If” paintings, I’m looking straight at the constantly metamorphizing, obfuscating cloud of these predictably unpredictable times and asking how best to live in them.

contact hypotheses

All That Is Solid

Using rocks as metaphors for all that we thought solid and lasting, I am painting my way through questions about the nature of permanence and equilibrium in human experience. Boulders and rocks placed in illogical and precarious piles allude to a growing sense of instability all around me. As the climate fluctuates wildly, democratic and cultural institutions show signs of structural strain and weakness, and the very idea of enduring truths wobble, I wonder aloud in my work where we are headed. Will we adhere to the ideals we once thought immutable or will we find ourselves in a time when, as Karl Marx observed, “all that is solid melts into air”?

Using rocks as metaphors for all that we thought solid and lasting, I am painting my way through questions about the nature of permanence and equilibrium in human experience. Boulders and rocks placed in illogical and precarious piles allude to a growing sense of instability all around me. As the climate fluctuates wildly, democratic and cultural institutions show signs of structural strain and weakness, and the very idea of enduring truths wobble, I wonder aloud in my work where we are headed. Will we adhere to the ideals we once thought immutable or will we find ourselves in a time when, as Karl Marx observed, “all that is solid melts into air”?

HalfEmptyHalfFull

Adapted from Terrain.org

It’s no accident that sometime around the 2016 elections I began to think about dams, particularly the Hoover and Glen Canyon Dams, both on the Colorado River. I looked to these audacious constructions inserted into the pristine Southwestern landscape as a way to consider our national identity at a turning point in both our political and environmental history. The HalfEmptyHalfFull paintings that emerged are relatively frontal, confrontational, and solid. The glowingly opaque dams meet the screechingly pigmented canyon walls and waterways along an electrifyingly sharp but wandering line of contact. To me, the dams speak loudly of our national urge to dominate nature in order to deepen our purchase on the land and create wealth. Starting with America’s 19th century white settlers and explorers, a steady stream of people spread out across the country, all eyes looking ahead without concern for the messy trail left behind. Operating under the protective umbrella of manifest destiny, we believed ourselves divinely entitled to alter the landscape by damming rivers and creating vast bodies of water, transforming the movement of water into energy, and transmitting that energy thousands of miles in order to build new cities in deserts. Whereas we once looked to nature for a sense of awe, these days we are more likely to look to the stupendous products of our own hands for that experience. The consequences of our actions have been mixed, a reality reflected in these majestic dams, both heroic and doomed. Some of the large ones, built to last 750 to 1,000 years, will most likely be decommissioned as climate change makes the water they depend on scarcer. But the sheer amount of concrete used in their construction makes the structures impossible to remove. The dams are beautiful, iconic forms that are likely to endure as monuments to our American hubris and greed—shortsighted interventions become leftovers in the landscape.

It’s no accident that sometime around the 2016 elections I began to think about dams, particularly the Hoover and Glen Canyon Dams, both on the Colorado River. I looked to these audacious constructions inserted into the pristine Southwestern landscape as a way to consider our national identity at a turning point in both our political and environmental history. The HalfEmptyHalfFull paintings that emerged are relatively frontal, confrontational, and solid. The glowingly opaque dams meet the screechingly pigmented canyon walls and waterways along an electrifyingly sharp but wandering line of contact. To me, the dams speak loudly of our national urge to dominate nature in order to deepen our purchase on the land and create wealth. Starting with America’s 19th century white settlers and explorers, a steady stream of people spread out across the country, all eyes looking ahead without concern for the messy trail left behind. Operating under the protective umbrella of manifest destiny, we believed ourselves divinely entitled to alter the landscape by damming rivers and creating vast bodies of water, transforming the movement of water into energy, and transmitting that energy thousands of miles in order to build new cities in deserts. Whereas we once looked to nature for a sense of awe, these days we are more likely to look to the stupendous products of our own hands for that experience. The consequences of our actions have been mixed, a reality reflected in these majestic dams, both heroic and doomed. Some of the large ones, built to last 750 to 1,000 years, will most likely be decommissioned as climate change makes the water they depend on scarcer. But the sheer amount of concrete used in their construction makes the structures impossible to remove. The dams are beautiful, iconic forms that are likely to endure as monuments to our American hubris and greed—shortsighted interventions become leftovers in the landscape.

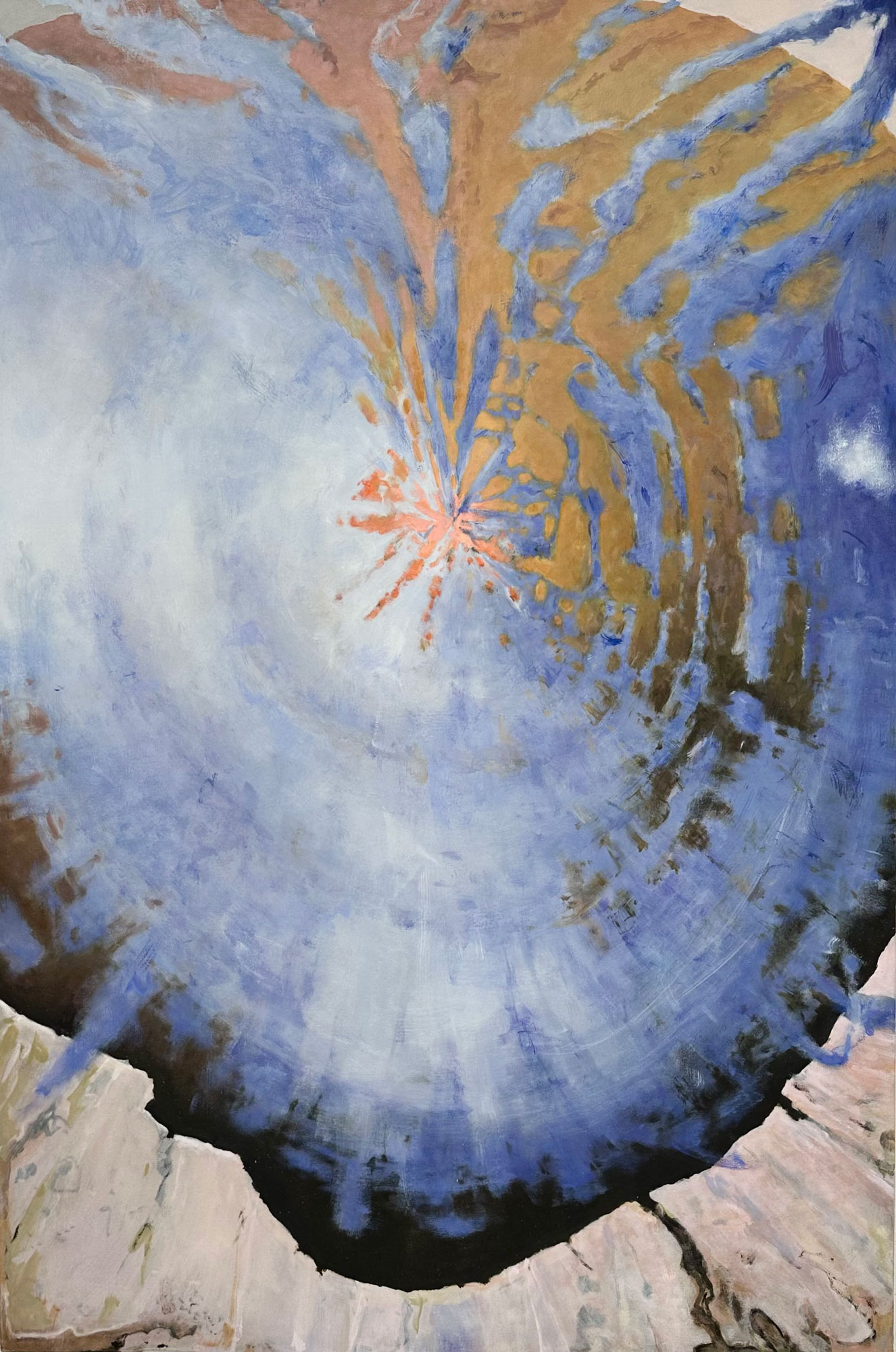

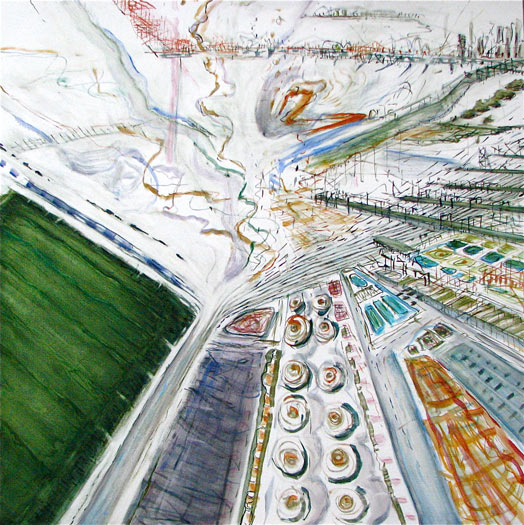

Edgelands, February 2013

My new work explores the complex relationships between nature and culture through the lens of the landscapes we have created. The current series investigates the edge lands where the built environment and the natural landscape converge, clash and interlace. The engagements that occur along such boundaries are dynamic, unpredictable and sometimes chaotic. Using a broad painting language of mark-making and a kind of bent, vertiginous perspective (often from an overhead angle) the paintings evoke a visceral sense of what it feels like to live in a landscape transformed by our own industriousness.

My new work explores the complex relationships between nature and culture through the lens of the landscapes we have created. The current series investigates the edge lands where the built environment and the natural landscape converge, clash and interlace. The engagements that occur along such boundaries are dynamic, unpredictable and sometimes chaotic. Using a broad painting language of mark-making and a kind of bent, vertiginous perspective (often from an overhead angle) the paintings evoke a visceral sense of what it feels like to live in a landscape transformed by our own industriousness.

While our culture generally likes to segregate the natural and the built landscape into discreet categories of experience– the sublimity of nature over here, the creations of civilization over there—the paintings map out how we have in fact jammed our manufactured landscape right up into the natural one and in the process they capture the kinetic energy and agitated motion many of us experience in our 21st century lives. Elements of order, beauty and exhilaration can be found in this world but there is also tension and disorder when these landscapes meet up, as well as a terrific energy in the friction the encounter produces.

The Panama Project, September 2015

on’t quite remember what caught my eye about the New York Times article a couple of years back reporting on the current expansion of the Panama Canal. The article explained how the project took flight in order to meet rising global trade demands and in response to the Chinese bid to build a competitive and route-shortening canal across Nicaragua. It could have been that the image accompanying the article was arresting or maybe the lively story of the canal’s history and its upcoming reinvention was what did it. In any case, I started to follow what was going on down there.

on’t quite remember what caught my eye about the New York Times article a couple of years back reporting on the current expansion of the Panama Canal. The article explained how the project took flight in order to meet rising global trade demands and in response to the Chinese bid to build a competitive and route-shortening canal across Nicaragua. It could have been that the image accompanying the article was arresting or maybe the lively story of the canal’s history and its upcoming reinvention was what did it. In any case, I started to follow what was going on down there.

For me, the canal is yet another of those complex landscapes rising around the world which embody what many scientists refer to as the Anthropocene– our current geological epoch in which human activity is the most dominant force shaping the earth. In the past, things like glacial or tectonic movement, naturally occurring weather patterns, or pre-eminent species of flora marked a particular epoch. Now, it is our own species that is most profoundly altering the planet and rocketing it into a new era.

Landscapes of the Anthropocene, places where the man made and natural landscape meet up, often uncomfortably, have been central to the imagery of my work over the last several years. The Panama Canal was intriguing to me for that reason and is why, early this year, I ventured to Panama City to take a look. As is generally the case, my direct experiences with the place trumped the expectations based on virtual encounters.

As anticipated, I did find the Canal Zone to be a particularly striking example of the kind of clashing landscapes I am currently drawn to – a visual feast for someone interested in expressing something about the way our civilization is inventing hybrid landscapes around the world. From high viewing points I could see the vast canal cutting through more or less pristine rainforest; and the severe rectilinear geometry of the locks literally stepping up and down through the muddy canal waters to enable gigantic freighters to pass between the Pacific to the Atlantic Ocean. There were also the expansive water containment pools and fuel tanks, as well as the gigantic port taking its place in a complex global transportation system. All of this added up to a kind of fantastical, brightly colored Lego land brought to life. My initial hill top view of the canal provided some dynamic visual information for my work. But I also had the chance to actually be on and in the canal and see things from an even more striking vantage point.

Through a friend I was introduced to a tugboat captain who invited me to spend a 10-hour shift riding on his boat, one of the many tugs working 24-7 ushering freighters and cruise ships through the canal. My day on the tug, more than any of the other experiences I had on or around the canal, is what has left the deepest marks on my thoughts and on my work. I spent most of that day sitting on the steps immediately outside the air-conditioned, technology-laden pilot room. I mostly just looked and took pictures, occasionally taking time out to step inside and pepper the captain with questions about the canal and his experiences. From my perch I could see and feel the life of the canal: enormous freighters carrying a vast array of goods passing both close by and at a distance; dredging boats excavating and spitting out its spoils to keep channels open; freight trains running parallel to the canal; tourist boats touting the fete of engineering that is the canal. I could also see the murky, strangely green water up close; experience the slow motion choreography of the ships as they moved through the locks with the aid of canal authority workers who looked like ants as they directed the elephantine dance in 90 degree heat. The ships’ crewmen appeared similarly dwarfed when they came into view high up on their vessels’ decks tying and untying towlines. And finally, there was the rain forest crowding in on the canal’s edge.

The tugboats’ main job in the canal is to help nudge the freighters into the locks, a surprisingly tight squeeze. The tugs are sleek pieces of machinery, able to maneuver razor sharp turns while generating terrific power to guide the giant tankers into place. Moving between assignments in the canal, tugs are frequently pulled behind those freighters, the most efficient way to make their way to their next lock job. During the middle of the day we spent a couple of hours in just such a position, tied up to the rear of an unimaginably large freighter that cradled a soaring pile of candy colored shipping containers. The vast hull of the ship and its contents entirely filled my field of vision. I could barely see around the edge of its mountainous geometric profile to catch a glimpse of the shore’s dense forest, parts of which are being sculpted by bulldozers into pyramidal forms to prevent erosion as the digging and dredging to widen the canal proceeds.

As I had observed from other viewing points, the very scale of the canal zone landscape renders the people involved in its operation almost invisible. This is a place outsized to everyday human life, but brimming with signs pointing to our human urge to explore, chase wealth and exert control over nature. Sitting there in the shadows of this hulking freighter, that sense of who we are was vividly confirmed. Staring at the massive hull made of impenetrable steel, painted a startling cobalt blue, I thought about the boat and its opaque belly filled with unknown contents. Where had it come from, where was it going, how much did it cost, who stood to benefit from its journey? While the engineering of the canal and its activity conveyed a sense of cheerful industriousness and purpose, the weight of large economic and political forces literally loomed over me with hints of menace. The apparent rationality of the canal landscape; the port with its tidy rows of packed goods ready to be loaded onto boats by a graceful army of cranes; the satisfying geometry of orderly stacked container ships along with the finely orchestrated passage through the canal, was wondrous to behold, but also, it seemed to me, dubious, the logic of its very existence open to question.

But experiences are not all one thing or another. In the midst of such dark musings, sitting in such close proximity to that container ship, I observed a surprisingly tender hint of humanity that belied my sense of doom. From my vantage on the water directly behind the great blue freighter, I could see how repairs made to the rust and contact damage sustained by the hull—rough traces of transatlantic sea passages and shorter passages squeezing through canal locks, revealed another story. Using a blue paint just slightly different in hue from the original color, some person had made broad gestural sweeps across the maritime scars. In doing so a gorgeous and compelling abstraction was created, a piece of floating art that highlighted the persistence of the individual’s touch and essential humanity even in the supermax world of global trade.

Overall, my visual experience of the canal felt like looking through an adjustable telescoping lens, seeing things that were both profoundly disturbing and exquisitely beautiful at different scales. My new body of work reflects this experience. I had the chance to observe the evolving canal landscape first from a-far, perhaps the most familiar vantage, then I got to take in the middle distance when I spent a day hiking with biologists on the Barro Colorado, an island in the middle of the canal that the Smithsonian operates as a Field Station to study the rain forest. From deep in the jungle here, you can spy freighters humming through the canal. And lastly I experienced the canal and its traffic at close quarters, sidling right up to the massive moving forms that are an essential part the Canal Zone landscape.

The work I’m making in response to my time in and around the canal attempts to simultaneously show the roaming point of view of the observer and that of a participant on the ground. But from any perspective, the pulse of amped-up human industry through a wildly diverse natural landscape beats ever more insistently. The Canal Zone is a place where nature has been profoundly altered, the landscape reconfigured by our industry and at our behest—since it is not just shippers and manufacturers who benefit from this landscape in one way or another but rather all of us. We need to look at our own implication in this and all the other novel man-made landscapes around the globe since they are the creations and products of our desires.

I think that the consequences of these desires and our industriousness, fully on view in the canal, haven’t been thoroughly processed or appreciated in the culture at large and specifically in American landscape art, with its traditional investment in a clear delineation between the products of nature and those of culture. The reflex response to these mongrel places is often simple dismay or disgust, but these landscapes are richer and more interesting than that, and more revealing. In these landscapes we get in touch with our human urge to push out and explore, as well as our will to dominate and exploit –and to make something entirely new. There is beauty in the unpredictable juxtapositions of rectilinear and organic form, the natural and the built, the wild and the tamed. This evolving landscape represents an extraordinary opportunity to reconsider our humanity here at the dawn of the Anthropocene.

Area of Concentration, October 2011

I wonder if the fact that I moved up onto a hillside in a city a few years ago is responsible for the paintings I’ve been making recently. These days I live in a house that commands an unfurling, aerie-like view of a big west coast landscape, spreading out onto what looks like a stage set. What I see out my window is a residential neighborhood dotted with giant elms sprawling down toward a bee-hive of industrial activity, freeways, train sidings, warehouse districts, factories, a landfill, a racetrack, ten-story-tall cranes loading freighters bound for China, bridges crossing the bay, two cities (one on each side of the bay) and finally, the hills of a national park. It’s a great stage for the meeting of man and nature.

I wonder if the fact that I moved up onto a hillside in a city a few years ago is responsible for the paintings I’ve been making recently. These days I live in a house that commands an unfurling, aerie-like view of a big west coast landscape, spreading out onto what looks like a stage set. What I see out my window is a residential neighborhood dotted with giant elms sprawling down toward a bee-hive of industrial activity, freeways, train sidings, warehouse districts, factories, a landfill, a racetrack, ten-story-tall cranes loading freighters bound for China, bridges crossing the bay, two cities (one on each side of the bay) and finally, the hills of a national park. It’s a great stage for the meeting of man and nature.

For years now in the studio, my focus has been very different: the intense close up view of common elements of the natural world—the bark of a tree, leaves, wood grain—in order to press an engagement with nature in everyday life. Now my mind’s eye has started to move up and out, to explore the long views afforded by my new prospect. Here, I see not just an idea about how we might engage as individuals with nature on the micro scale, but how the larger culture plays out its relationship with the natural world in our time. The picture is both exuberant and terrifying.

Formally, I see lots of interesting parallels and continuities between the built and the natural landscape. Patterns and configurations echo and rhyme. Traffic arteries and rail lines suggest water courses; striated cliff faces intimate blocks of city buildings; the cellular honeycomb structure of a rotted tree trunk resonates with the open lattice-work of a building under construction; the urban grid from above could be the motherboard of a computer or plant tissue as seen through a microscope—the list goes on and works at a variety of scales. Motion also suggests lines of connection between these two supposedly warring realms: our pulsing movement through the landscape (by car, train, boat, fiberoptic cable) mirrors the lines of force in rushing water, the flow of sap through the vascular system of plants, even colonies of bacteria on the move.

My last series of paintings, Through Lines paintings, explored these echoing patterns of cultural and natural form at scales left deliberately ambiguous. The current series, Area of Concentration, seeks to dramatize the relationship, sometimes clashing, other times soothing, between these elements, elements that our culture usually likes to keep apart: the beauty of nature over here, the creations of civilization over there. Yet, there is beauty, we well as tension, when the two come together, and energy in the friction that meeting produces. From my vertiginous perch up on a hill—in an earthquake slide zone—I look out at an area of intensely concentrated life, and can’t overlook the potential for chaos and destruction that can come (perhaps has already come) from having thrust ourselves, so industriously and so cavalierly, into the natural world.

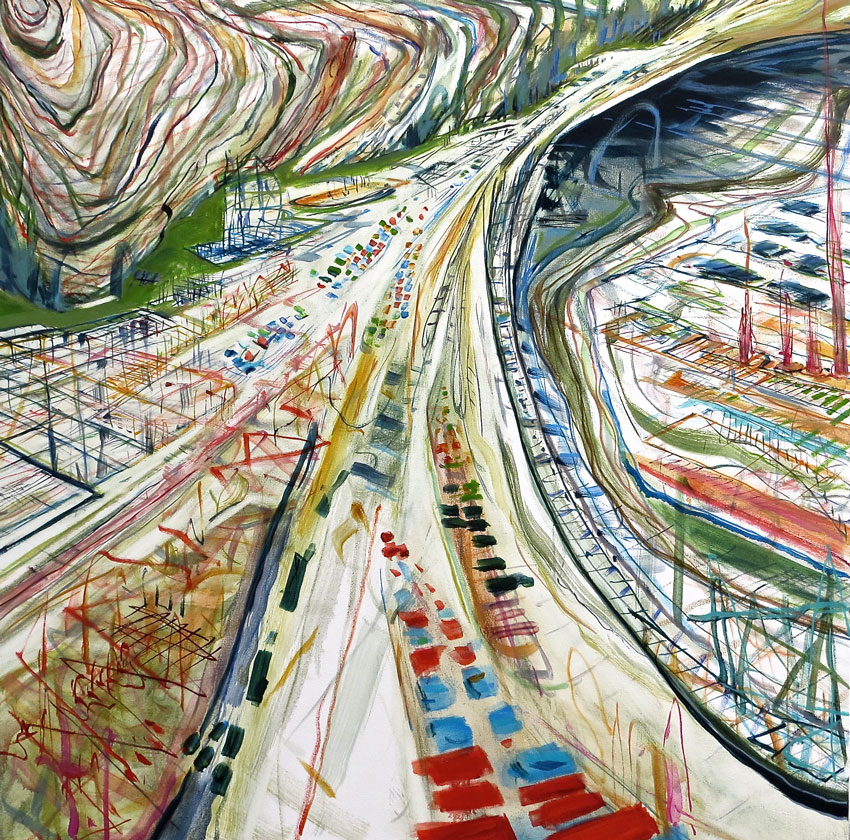

Through Lines, January 2011

maps,architectural constructions). Shuttling between a micro and a macro scale while using a shifting perspective, the work has shed a literal context in order to explore certain ambiguities in the way we experience the world. Is what I’m looking at animal, vegetable or mineral? Am I looking through the lens of a microscope, from the windshield of an airplane cockpit, at a computer-generated landscape or an object in the palm of my hand? The paintings employ the language of drawing to delve into the visual continuities between such disparate things as a chunk of rotting oak tree, a bacteria cell division, a massive granite outcropping, and a freeway interchange. What emerges from this inquiry is a through line linking the organizing principles of both the natural and built environment.

maps,architectural constructions). Shuttling between a micro and a macro scale while using a shifting perspective, the work has shed a literal context in order to explore certain ambiguities in the way we experience the world. Is what I’m looking at animal, vegetable or mineral? Am I looking through the lens of a microscope, from the windshield of an airplane cockpit, at a computer-generated landscape or an object in the palm of my hand? The paintings employ the language of drawing to delve into the visual continuities between such disparate things as a chunk of rotting oak tree, a bacteria cell division, a massive granite outcropping, and a freeway interchange. What emerges from this inquiry is a through line linking the organizing principles of both the natural and built environment.Trees Inside Out, March 2009

“Trees Inside Out”, my installation at Dosa818 in downtown L.A., employs architecture, drawing and painting to explore our relationship with nature. The painted images of tree bark, set into the hand-drawn plywood walls of two, small structures –one squat and stump-like, the other shooting upward– might clue you in to what you can expect to see once you step up and inside. Entering the intimate, protected space within, you are invited to take an imaginative leap into the center of a tree. And in fact, there inside, you’ll find several painted images on canvas that are about wood: tree rings, wood grain, and other patterning that might or might not be recognizable as specifically tree-like. As you look at the paintings, housed within these structures made from thin slices of tree glued together (plywood), you are invited to think about trees and wood from the inside out, in its most natural, pristine form as well as its most mundane industrial application. “Trees Inside Out” brings painted images of natural forms, as well as elements of unreconstructed nature, into a constructed urban setting and asks us to consider just how entwined nature and culture are in our everyday lives.

“Trees Inside Out”, my installation at Dosa818 in downtown L.A., employs architecture, drawing and painting to explore our relationship with nature. The painted images of tree bark, set into the hand-drawn plywood walls of two, small structures –one squat and stump-like, the other shooting upward– might clue you in to what you can expect to see once you step up and inside. Entering the intimate, protected space within, you are invited to take an imaginative leap into the center of a tree. And in fact, there inside, you’ll find several painted images on canvas that are about wood: tree rings, wood grain, and other patterning that might or might not be recognizable as specifically tree-like. As you look at the paintings, housed within these structures made from thin slices of tree glued together (plywood), you are invited to think about trees and wood from the inside out, in its most natural, pristine form as well as its most mundane industrial application. “Trees Inside Out” brings painted images of natural forms, as well as elements of unreconstructed nature, into a constructed urban setting and asks us to consider just how entwined nature and culture are in our everyday lives.The Inner Life of Trees, March 2008

Maybe it’s just me, but the idea of crawling along the bark of a tree and then, somehow penetrating to the tree’s interior is enticing, even thrilling. I would find myself exploring an alternate landscape, completely strange and yet in some respects peculiarly familiar. Would I be a tiny ant-sized being gazing upon monumentally scaled ridges, peaks and valleys busily pushing their way through space, or would I be a giant looking, as if through a microscope, at pulsing veins of energy in constant motion? I imagine it might be an unlikely combination of the two perspectives. My tree fantasy returns me to elementary school science class and to words like cambium, xylem (up) and phloem (down), and then pitches me forward into a horror movie in which the heroic trees are striving madly to suck carbon from the atmosphere as fast as the humans and their infernal machines can spew it out.

Standing stick with stuff on top ~

Standing stick with stuff on top ~

’s us and them. The international symbol for “tree” and the one for “man” are easy to confuse.

New horizons ~

’m arranging many of my new paintings in series that form a line across the wall; some others are single paintings severely horizontal in format. These groupings and individual long pictures form their own horizon lines on the wall rather than in the painting. The aim is to suggest an alternative landscape into which the viewer is drawn right up into, so that it fills one’s peripheral vision. This approach to the presentation of nature presses against the conventions of landscape painting in which nature is neatly ordered around a horizon line located in the distance of the pictorial space, approached by following an illusionistic path leading through a foreground to the middle distance and beyond.

Serial looking ~

This serial framework suggests the unfolding of a story. In this story, there is no single way to look at nature. There’s this vantage point, and then there’s that one, as you move across the visual plane. The ability to consider nature in this way is probably the gift of photography. Photography introduced the idea of multiple perspectives and represented a deep shift from what the painted landscape had offered previously. In my work, the multiplying viewpoints remind us how nature defies a static reading or stable perspective. It’s not just we animals that are animate; we are just a part of the story. Plants are another, and they are agents of change too.

Nature is Busy ~

No one view of nature prevails because nature itself- not just the observer- is constantly changing. Living species are engaged in a continuous process of metabolizing and reproduction, doing what it takes to keep going. The minerals and gases are changing too. While we humans might think everything revolves around our own life cycles, we are just one player in nature going about its business. The patterns found in nature –whether wood grain or ripples in sand or striated rock formations– dramatize this constant activity, a pushing and pulling that occurs at every scale of time— with the tides in the ripples on the beach, with the earth’s unpredictable jolts to it’s crust, with the years in the grain of wood.

Ditto, almost ~

It’s surprising to me that while painting what I imagine to be going on inside the tree, I find all kinds of patterns or forms I’ve observed elsewhere in the natural world. I am reminded of things like stone outcroppings, sand dunes, shells, water, human body parts, and feathers. And then there are the echoing graphic patterns found in our various depictions of natural phenomena, such as the isobars on weather maps, topographical elevations and ocean floor charts. I’m not sure why there are all these repetitions, but it’s interesting to locate them and consider the reasons why evolutionary forces seem to share common patterns across the spectrum of nature.

Trees/wood/lumber/pulp ~

Some of the paintings offer a view of wood that would be impossible to obtain were it not for the work of a saw or some other human tool. Wood is in my everyday life everywhere I look. There it is under my feet (floorboards); now I’m sitting on it (chair); it’s in my hand as I work all day (paintbrush handle); there are the trees planted in a line down my street to shade the sidewalks (elms); and now it rests on my chest before I drop off to sleep (book). Wood and human culture rub up against one another in an almost constant and unavoidable dance.

Heavy lifting ~

But even standing uncut or lying fallen on the forest floor, the trees play an ever-present role as symbols of our shifting cultural values and concerns, a storehouse of particularly rich metaphors. They embody human views of nature that range all the way from the romantic and sublime to the apocalyptic. Trees have served variously as symbols of history and continuity, of precariousness and peril, of culture and political stability, and of wilderness. Trees are also seen as benevolent timekeepers, benign habitats for all manner of creatures, respirators, healers of human ecological harm, and by some, as symbols of god’s handiwork.

Ride the wave or what? ~

I experience nature as a roiling, forceful energy that is extraordinary and yet also an ordinary part of everyday life. Is that because I somehow impose my own psychological state on what I observe every time I walk out my door? Lots of people assume that nature is something found only in wilderness parks, unchanging and saved for vacation days. In any case, during these times of mounting worries about the degradation of our local landscapes, an intimate engagement with nature, a recognition of the active part it plays in our daily experience, seems particularly urgent today. Don’t we need to come to an understanding about how to live in a truly reciprocal relationship with other species— if only for the self-interested reason of our own survival?

Ant or giant or both II ~

So, right now, I’m looking to the trees for some information. However I look at these prominent figures in our landscape I cannot help but feel how important they are. Trees. Whether majestic or lowly, I sense their complicated inner lives. The drama of how they chart their course through space, the secrecy of their hollows and fissures, the intricate designs of their growth patterns, and the magic of their biochemistry—all tell a compelling story. Maybe it’s just me, but I think it’s worth crawling over the bark and finding a way in to observe what’s there, in the center of the trees.

Post-Romantic Landscapes, January 2007

In my current work I am focusing my gaze on large western trees, because they are, for me, the figures in the landscape from which we can glean some of the most important information about a place and its natural history. Their very girth reminds us of nature’s force and how inconsequential our attempts to exert control over it can be. The newest paintings explore the eucalyptus, a strange and beautiful species that carries a contradictory set of associations here in northern California, where the beauty of its peeling bark and elephantine forms is inflected by the knowledge that the species is invasive and highly flammable. Trees have always served as important symbols of our shifting cultural values and concerns, embodying views of nature that range all the way from the romantic and sublime to the apocalyptic. For me, big trees have two faces: history and continuity on one side, precariousness and peril on the other. We fear the loss of our great trees in fires and storms (made more violent by climate change), and, especially in the West, we fear the destruction they can wreak on familiar landscapes and our homes. But we also look to the trees as giant, benevolent timekeepers and witnesses of our personal and natural history. The trees are the planet’s great respirators (and keepers of carbon) as well as emblems of social and ecological stability. Theirs trunks are virtual maps of time, their intricate patterning reflecting the vagaries of the local environment over time; their great limbs reaching into unclaimed spatial territory, their hollows and stumps disclosing the ghosts of past disasters. Prominent figures in our landscape, trees project endurance and beauty, but also a menace and, increasingly, our worries about the future.

In my current work I am focusing my gaze on large western trees, because they are, for me, the figures in the landscape from which we can glean some of the most important information about a place and its natural history. Their very girth reminds us of nature’s force and how inconsequential our attempts to exert control over it can be. The newest paintings explore the eucalyptus, a strange and beautiful species that carries a contradictory set of associations here in northern California, where the beauty of its peeling bark and elephantine forms is inflected by the knowledge that the species is invasive and highly flammable. Trees have always served as important symbols of our shifting cultural values and concerns, embodying views of nature that range all the way from the romantic and sublime to the apocalyptic. For me, big trees have two faces: history and continuity on one side, precariousness and peril on the other. We fear the loss of our great trees in fires and storms (made more violent by climate change), and, especially in the West, we fear the destruction they can wreak on familiar landscapes and our homes. But we also look to the trees as giant, benevolent timekeepers and witnesses of our personal and natural history. The trees are the planet’s great respirators (and keepers of carbon) as well as emblems of social and ecological stability. Theirs trunks are virtual maps of time, their intricate patterning reflecting the vagaries of the local environment over time; their great limbs reaching into unclaimed spatial territory, their hollows and stumps disclosing the ghosts of past disasters. Prominent figures in our landscape, trees project endurance and beauty, but also a menace and, increasingly, our worries about the future.